Early January television is usually sluggish, a desert of half-hearted premieres and uninspired leftovers. So the arrival of His & Hers on Netflix, slick as lacquer and already perched at the top of the platform’s Top 10, feels like a small cultural gift. Adapted from Alice Feeney’s bestselling 2020 novel and produced by Jessica Chastain, the six-part thriller is a perfect binge for the foggy liminal weeks after the holidays: propulsive enough to entertain, dark enough to intrigue, and stylish enough to justify its own excesses.

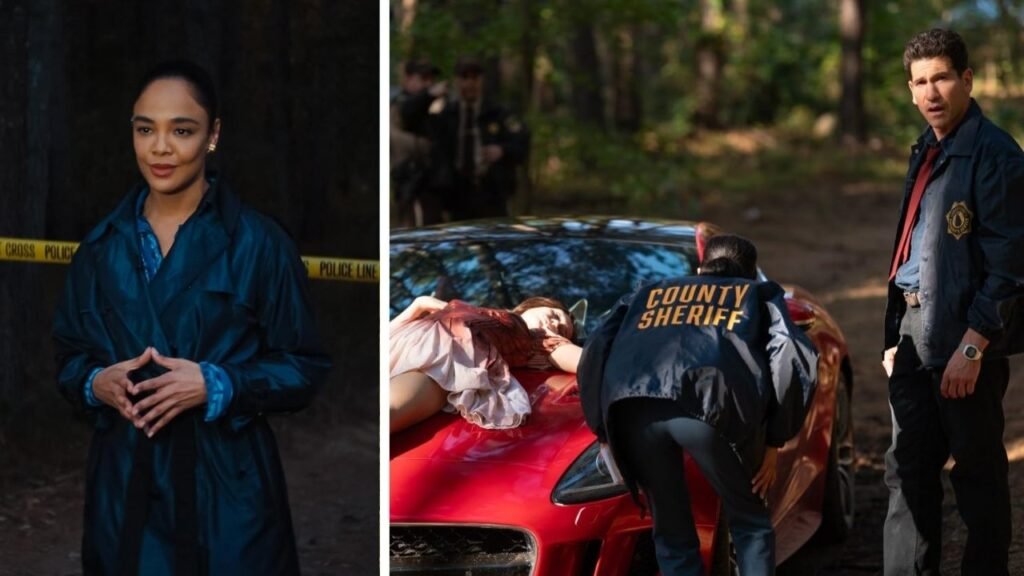

It opens with a tableau ripped from a crime novel: a woman gasping her last breath on the hood of a car, deep in the woods. Soon after, another staggers into her immaculate apartment covered in blood, panic, and expensive wine cravings. “There are two sides to every story,” a disembodied voice purrs. “Which means someone is always lying.” It’s an absurd thesis, but also the show’s promise: don’t expect realism, expect a game.

Estranged Lovers, Shared Lies

Our players are Jack Harper (Jon Bernthal), a small-town detective, and Anna Andrews (Tessa Thompson), a once-scorching news anchor now fighting for relevance after grief derails her career. The pair share a marriage that once had heat and now holds only ash, estranged, but not enough to sever emotional stakes. Their professional rivalry becomes entwined with a murder that unfolds in their mutual hometown, a place where adolescent sins were never exorcised, merely stored underground like toxic waste.

Thompson and Bernthal do not play this as noir-archetype exes but as two people convinced they know each other too well and not at all. Their mutual suspicion gives the show its electricity; at certain points, the viewer cannot rule out either as the killer, which is both narratively satisfying and psychologically pointed. Trauma, the show suggests, can make strangers out of intimates.

High School Queens, Adult Corpses

The mystery revolves around Rachel Hopkins, former queen bee and first casualty. Hers is a death that echoes backwards, summoning a clique of women who once ruled their prep-school halls with the ruthless precision of sorority tyrants. Feeney’s novel already understood the particular cruelty of female adolescence; the series embellishes it with visual menace, glossy yearbook smiles, weaponized popularity, whispered rites of humiliation.

The suspects accumulate with pulp efficiency: cuckolded husbands, bitter friends, jealous rivals, and yes, even Anna herself. It’s a whodunnit, yes, but by Episode Three, the question shifts subtly into why and for what debt.

Though Feeney set the novel in a British village, William Oldroyd’s adaptation moves the drama to Dahlonega, Georgia, a decision that pays dividends. The Southern setting adds humidity, literal and emotional. Gossip here is currency. Secrets rot more slowly in the heat. And the lake house, central to the final episodes, feels less like a location than a haunted memory made architectural.

Netflix thrillers often flatten space; His & Hers gives geography texture.

The Mother Who Kills for Love

Much has been made of the show’s twist — that the killer is not Lexy, the rebranded school outcast, but Alice: Anna’s own mother. It’s a reveal that recontextualizes the entire narrative and transforms the series from glossy murder puzzle into something close to Greek tragedy. Alice’s motive for vengeance for the assault Anna endured as a teen makes the killings not about mystery but restoration, a grotesque act of maternal correction.

What could have been gratuitous is handled with surprising tact. Through old tapes and fractured memory, the show invites the viewer into a question far thornier than guilt: What is justice when institutions fail? And who gets to deliver it?

Oldroyd has called his adaptation a “love letter” to mothers. It’s a wild claim on the surface, the woman kills multiple people and frames another, and yet the finale makes it feel disturbingly genuine. Thompson plays Anna’s realization not with horror, but with a grim, almost reverent recognition. Some debts, the show argues, can only be paid in blood.

Domestic Noir, Elevated by Performance

Thompson anchors the series through emotional gradients of ambition, shame, rage, and survival without ever collapsing into melodrama. Bernthal, meanwhile, excels at portraying masculine woundedness without leaning on cliché. Their performances turn the twisty plot into something more like a character study

Around them, the supporting cast enriches the ecosystem: Marin Ireland’s alcoholic Zoe is both monstrous and pitiable; Pablo Schreiber’s Richard is equal parts pawn and provocateur; Rebecca Rittenhouse’s Lexy plays duality like an art form.

Binge TV, But With Aftertaste

Most thrillers end where the mystery ends. His & Hers refuses. It flashes forward to a year of tidy domestic renewal, new baby, new house, adopted daughter, careers restored, and then punctures the veneer with the unspoken: Jack still doesn’t know Alice killed his sister. Happiness sits atop a charnel house.

The show’s final, wordless exchange between Anna and Alice is chilling, tender, and deeply earned. It asks the viewer to consider what love can justify, and whether secrets preserve families or poison them.

Verdict

His & Hers is glossy entertainment, yes. It’s bingeable, absurd, twist-drunk. But beneath the pulp lies a surprisingly resonant meditation on girlhood cruelty, survivorhood, maternal ferocity, and the impossibility of clean justice. It’s domestic noir with teeth, and it lingers longer than it has any right to.

Watch if you love:

Gone Girl, Big Little Lies, Sharp Objects, The Undoing